The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (1982, 2003)

The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.

So much potential in that opening line, words bending worlds with such heft and grace and unblinking audacity. The Gunslinger is chock full of lines like this ("Go, then. There are other worlds than these." *shiver*), moments that bear the weight of millions of swirling galaxies, the dazzling, dizzying spell of Walter's whipcrack tour of infinity all balanced on the edge of the shift-T on Stephen King's rickety old "office-model Underwood with the chipped 'm' and the flying capital 'O.'" (King, "Afterword," The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger, c. Donald M. Grant, 1982). He set that sentence to paper during his senior year in college and, whether he sensed it or not, his grand opus had begun.

This post will no doubt reflect the wildly schizophrenic relationship I've had with The Dark Tower series since day one, specifically because it centers on the introductory novel that kicked it all off . . . and the revised edition King felt compelled to publish twenty years later. King's own assurances that the changes were, indeed, a "mere thirty-five pages" (and nothing in comparison to the revised edition of The Stand) are even less a comfort when he goes on to say that he's less concerned with the possible grumblings from the "purists" than with the "readers who have never encountered Roland and his ka-tet" (King, "Foreword," The Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger, Revised and Expanded Throughout, Plume, 2003).

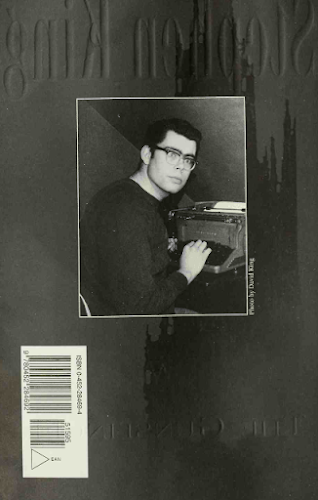

|

| Wee baby King! |

First of all: Wow. Okay. Snotrockets launched, I see. Noted. Let's assume this completely unnecessary barb was due to some residual defensiveness having just completed the last two works in the Dark Tower series at the time he wrote the preface for the revised edition of The Gunslinger. He knows he did a bad thing. Even if he doesn't know it, know it. We'll talk about The Bad Thing in some future post, after I've endured the Song of Susannah once more. I've only read it one time. I was so angry I almost levitated.

Snotrockets be damned, I was happy to read The Gunslinger again. It had been awhile since I'd stepped into the shadow of the Dark Tower (I think I made an attempt during the dark days between 2008-2014, though I am not sure--if I did, I didn't make it far) so I was eager to get back to the source material and embrace dusty old Roland and his crooked world the way I once did, before things moved on, as it were. Before the movie happened, for instance.

Sometimes I talk about the movies, sometimes not, but in this case I'm going to keep it brief: I didn't like it. I wanted to like it. I had hopes. Not high hopes, mind you, but guarded hopes. The casting was magical and brimming with possibilities; Idris Elba's cool charm, Matthew McConaughey's glittery-eyed fervor . . . they just needed to be wound up and set in the right direction. Decisions were made and a terrible, terrible film flopped out of the hybrid nightmare factory, pulled its jittering carcass across the screen, and died in our memories foreveraftermore. At least that's what happened for me. I saw it in the theaters, got a stomach ache, then forgot almost everything about it. After it was released on DVD I picked it up at the library to see if a second viewing would change my opinion. It didn't. Most of it has, yet again, fallen out of my head and evaporated into the ether. I couldn't tell you the plot to save my life. The one thing I enjoyed--the one and only thing--was the depiction of Roland's shooting/reloading abilities. They got it deliciously right, which made all the rest of it so much more disappointing.

This leads me to The Problem at hand, and one of the reasons that movie will not stick no matter how many times I watch it. Those "mere thirty-five pages" in the revised edition of The Gunslinger are primarily meant to sync the first book with themes King introduced later in the series. Most of these themes (and details, and dialectical conventions) don't start popping up until after the third book in the series, The Waste Lands (1991). It wasn't until 1994's Insomnia that some of those major themes (the Crimson King, for example) started to appear in any of King's works. After that, all bets were off. There is an exhaustive list of connections between the Dark Tower books and the rest of King's work, but chronologically I'm pretty certain it all started with Insomnia. The latter books pull characters and references from earlier King works, and the revisions introduce them, but the nexus in real time is Insomnia.

I liked The Gunslinger, a novel I'd eventually gotten around to reading sometime in high school, but I absolutely adored next two novels in the series, The Drawing of the Three (1987) and the aforementioned Waste Lands. I finally scored the paperback for Drawing of the Three early in my freshman year in college (1990) and devoured it like air, then waited impatiently for the paperback of Waste Lands to release in the Spring semester of my sophomore year. It was more than I could have hoped for: transformative, joyous, wild, terrifying, everything. What an epic this was turning out to be. What a magnificent yarn.

Have you ever heard the phrase "Now we're cooking with gas"? I imagine someone believes this is true. I didn't dislike the rest of the books in the series, but the addition of the Crimson King, the low men, Father Callahan, and other random elements of the chronicle leave me slow mutant rubbery cold. Wet raspberries for everyone. Now we're cooking with fart gas. I remember little snippets of the remaining novels, a bit here and some more there, but most of it a blank to me. I remember some plot points, some deaths, and that one Very Bad Thing that made me absolutely furious, but a lot of it is a mystery. Like the movie, those last books in the series just slipped right off the surface of my brain. I've never even read the come-lately book 4.5 Wind in the Keyhole. I bought it and it grew a velvety coat of dust on my shelf.

So I took King's word for it, even after he gently dismissed the loyal readers from ago, and went ahead and dove into the 2003 revised edition of The Gunslinger for this chronological reread of all things Stephen King. Cleaning up factual errors and aligning book one with the latter books in the series was not the end of it, however. If that had been the case, I could have just rolled with it. Unfortunately, there was also strange tinkering with character development and details that should have been let stand. For want of an editor with a big red pen to STET STET STET all over that revised manuscript, the gunslinger was skewed soft and blurry, and for no damn reason at all.

I knew it was off from the start; the modifications and omissions were impossible to ignore. While I didn't have the original edition of The Gunslinger memorized, I have read it at least seven times. I am sure I am not the only fan who would go back and reread the previous volumes in the series before breaking open the brand new one from the bookstore. I would plan ahead, checking the pub date and starting off with The Gunslinger a couple of months (or more) ahead of time, followed by Drawing of the Three, The Waste Lands, and so on and so on. Since the last two novels in the series were released just a few months apart, I read them together as one very long tome . . . after I'd finished my last read through of the four proceeding novels. The Gunslinger isn't memorized, but I know it, you know? It's a familiar room in the rambling manse of my brainworks.

Some very kind and patient souls put together a list of most of the revisions on ye olde TheDarkTower.Net, but they missed a few, the first of which I noticed because it struck me so odd every time I read through The Gunslinger anew. On only the second page of the tale, Roland is brooding about the campfires left behind by the man in black, and he wonders if they are "a message, spelled out letter by letter. Take a powder. Or, the end draweth nigh. Or maybe even, Eat at Joe's. It didn't matter." In the revision, the quirky reference to our world is gone: "Perhaps the campfires were a message, spelled out one Great Letter at a time. Keep your distance, partner, it might say. Or, The end draweth nigh. Or maybe even, Come and get me. It didn't matter what they said or didn't say."

|

| Clearly this is about more than just being a kid when King first set out to write The Gunslinger. Not to worry, this won't be the last reference to the ominous "nineteen." |

In this case, replacing the "Eat at Joe's" reference is a sound decision. It never really fit. Too casual. Too out of the blue. Later, when people in a bar are singing "Hey Jude," the reference becomes all the more curious. This isn't our world. Or is it? One could fathom a Beatles song surviving eons, like a lullaby from centuries past, but "Eat at Joe's"? Or is this another world entirely? Are these just echoes of shared culture across time and space? On page two of the first book in the Dark Tower series, the reader simply does not know. It is all on the horizon, yet to be discovered. The "Eat at Joe's" reference was jarring and it had to go.

But take note of the additions, too, and how the once economical reverie is suddenly burdened with exposition that needlessly slows the pace. There are cuts, additions, and revisions throughout the novel that simply do not belong and speak more to a heavy-handed, highly biased perspective than to a clear eye with full-scope knowledge of what might benefit this particular part of the story, sync it naturally to the latter novels, while retaining the overarching voice and pacing of the original.

One of the most riveting parts of The Gunslinger is when Roland meets 10-year-old Jake at the Way Station. The abandoned structures are in the middle of literal nowhere, with desert surrounding for miles in every direction, and the boy is lost in every way he could be: time, space, and mind. He's been stranded alone for days, maybe weeks, and as time progresses, he loses memory of the place he existed before the new and terrible now. Roland hypnotizes the boy and the narrative transitions into an italicized dream sequence, skittering through a whirlwind of gutting worldly facts and cutting personal revelations. The revelations that Jake is from our world and not Roland's come fast and hard. The careening perspective from the dry desert nothing to the shining 1970s skyscrapers of New York are dizzying and electrifying with implications. Just what the hell is going on here? How did the kid get there? Why? It sizzles and sparks.

|

| This is page xxviii (28) of the prelims, verso to the next page which serves as a sort of subtitle to this first installment of the Dark Tower series. |

But this part of the narrative relies on the matter of fact, ruthless pace, each fact slamming into focus as the next comes swinging all sharp edges and more alienated from Roland's world than the last. In the original version, King cuts a quick sketch of Jake's father in hard, bludgeoning strokes: "His father works for The Network, and Jake could pick him out of a line-up. Probably." In the revised version, he expands: "His father works for The Network, and Jake could pick him out of a line-up of skinny men with crewcuts. Probably." The first version is telling and brutal. The second softens it for no discernible reason.

I could stand the additions and revisions that align The Gunslinger with the rest of the series, even if I don't particularly think much of it is cooking with gas per se, but there were a couple of changes that were just complete nonsense. King, for reasons I cannot fathom (but will perhaps be clearer when I reread the rest of the series?? maybe????), was compelled to modify aspects of Roland's character. If these declawing measures were consistent, maybe the reader could accept them (begrudgingly), but this is not the case. A minor change occurs during the flashback to Roland's coming of age, after he's bested his instructor Cort with the aid of the hawk David. The animal does remarkable damage to Cort, but does not survive the fight. Roland's friend Cuthbert asks if he would like help burying David. In the original, a very Roland "Yes" was the response. In the revision, Roland says, "Yes . . . That would be lovely, Bert."

|

| In the same realm of whyyyy as the epigraph: this. |

It struck me so strange I had to look it up. Luckily for me, there is a PDF of the original up on the web (it won't last, they never do). Is it impossible that Roland would suddenly transform into a cordial, drinks-on-the-veranda 50s housewife immediately after a bloody all-or-nothing showdown where the stakes were his whole future and the cost was his hawk friend, David? Is it impossible that the usually stoic, reticent Roland who kicked in Cort's door with murder for another on his mind, his blood boiling, and now beaten, cut, bruised, but triumphant, would suddenly turn into a kindergarten teacher thanking her little students for pushing in their chairs after snacks? Thank you, Bert, for helping me bury my bloody, twisted, murdered hawk which is one hundred percent my bad, ha ha, THAT WOULD BE LOVELY.

|

| The gloss insert, full color art is phenomenal, but I've love the inset black and white sketches the most. They only get better from here. All art copyright Michael Whelan. |

No, not impossible. Just not true to the character. And lest you think I nitpick, the very worst alteration to Roland's character is yet to come. This one is widely documented and well known. Most references to it across the internet have stayed diplomatically neutral, but no. Can't. Won't.

On his way across the desert, on the trail for the man in black, the gunslinger comes upon a town called Tull. The man in black has left his mark by way of resurrecting the town drunk (or the Mid-world equivalent, devil grass addict) and allegedly impregnating the resident religious cult leader. Roland stays in town longer than he intended, mollified by the attention and bed of Allie, the proprietor of Tull's only barroom. Roland eventually forces his own hand by confronting and assaulting the cult leader to get more information about the man in black and the whole town (save poor Allie) turns against him. In the original, as the crowd closes in, all brandishing some sort of weapon (though never guns, which are dear in Roland's world), the gunslinger's reaction is "automatic, instantaneous, inbred" and he begins to fire even as he sees Allie being held as hostage and shield, pleading, "'He's got me O jesus don't shoot.'" He guns her down with the rest of them, "the hands were trained."

|

| Messiah Gunslinger |

It is a painful moment for the reader, not that Roland's done much to garner sympathy already, but it reveals the gunslinger's past as much as anything, the training, the years between, the struggle and survival. In the revision, the showdown rolls out the same as before, but instead of pleading for her life, Allie screams, "'Kill me, Roland, kill me! I said the word, nineteen, I said, and he told me . . . I can't bear it--' The hands were trained to give her what she wanted."

Let me stop a second and breathe. If I could punch a sentence in the face . . . well, that would be lovely.

This circles us back to The Problem, e.g. the sort-of matchy, half-baked themes that snaked their tendrils through so many of King's works and became, for better or worse, central to The Dark Tower narrative. In the original Gunslinger, the man in black, Walter, may be the same as the dark man (i.e. Randall Flagg from The Stand) but it's never an established fact. A fan could draw a conclusion, but only if you are really vibing for interconnected story lines and fun Easter eggs. And he is never identified as Marten, the duplicitous usurper behind the upheavals the drove Roland from home and toward his eventual quest to find the man in black. But in the revision, Walter is revealed to be Marten (not in a particularly well executed way, either, which confuses the reader and makes her back track to reread these parts again and wonder whhhyyyy someone didn't fix it before sending this edition to print). In later books, Walter is also revealed to be the dark man, Randall Flagg, the Walkin' Dude because why not. And just like the "nineteen" story that drives Allie mad, it's shoehorned in there with a battering ram.

|

| "There the gunslinger sat, his face turned up into the fading light (the gunslinger and the man in black)"--last glossy insert, copyright Michael Whelan. |

Was it so essential to ensure that Roland could never be so bad that he'd (unintentionally or not) shoot his lover in the in the middle of a town-wide melee? Could the reader not empathize with his plight, the turn of the wheel of ka, the brutal, immediate reality of the situation? The disgusting rape/abortion scene with the cult leader that precedes the town showdown is still in the revised edition, so I'm not sure that changing Allie's fate helps all that much, especially when followed by "his hands were trained to give her what she wanted." In light of what he's already done in Tull, this just makes it worse.

Or was this more about that "nineteen" subplot, the silly, capering clown note from Walter practically daring Allie to speak the incantation that would bring with it unbearable truths from the afterlife? As I said, I don't remember much after The Waste Lands, so maybe that's where the compulsion to jam this revision in there lies. Whatever the case, it's a bloated square peg hammered into a broken round hole. I would think even a first-time reader would see the seams, where the new overlays the old, where the economy of words and emotion are metered, then flattened by a fatuous overextension of "corrections."

|

| The revised Gunslinger came out between Wizard and Glass and Wolves of the Calla (Wind Through the Keyhole wouldn't exist until ten years later). |

It is all the more baffling that King decided to add an all-new epigraph to kick off the revised edition of The Gunslinger. The original didn't have one. The revision shouldn't have one. It is a quote from Thomas Wolfe:

The epigraph is certainly relevant to The Gunslinger, sure, but even more slyly relevant to the Dark Tower series as a whole. I may not remember much of the latter books, but I remember what happens to Roland at the end. A lot of people were Very, Very Mad about it, but I wasn't one of them. Considering the entirety of the work, it fit. I won't spoil it here, except to say that Stephen King seems to be trying to spoil it for everyone with the very first epigraph in the very first (revised) book in the series. I could see why he dug the quote, why he wanted to include it, but it skates too close to saying too much . . . and for what? That little, winking zing of relevance? I think back to that new line from Allie, where she begs to be killed, "I said the word, nineteen, I said" . . . as if we wouldn't remember. Or were too dumb to make the connection from a few short pages back. Doesn't he trust us?

|

| Hands down, one of my very favorite author photos. |

It should go without saying that everyone can choose their own path: read the original, read the revised edition. Both editions are out there, though the first is obviously out of print. I will choose to reread the original should I ever wish to take this path again, clutch my tattered old original paperback copy close and go cry in a corner. It doesn't matter. The stories, and the very best parts of them, which still stand and set the world to quake with all that beautiful, shattering world building--dream infused, winsome and dangerously wild--are still a hot ride: emotional, riveting, bold, true. It's important to note that. My love is querulous and cutting, but it's is forevermore true blue.

Grade: B (for the original--it wouldn't be fair of me to grade the revision when I'm so clearly biased against it)

Scary? (0-nope to 10-you will die): 1. While there are intense scenes of violence, even the scariest stuff (slow mutants) isn't terribly scary.

Warnings: Heavy-handed tinkering, irrational editing, forced revisionist tomfoolery, author-induced spoiler alerts, cockadoodie rewrites. On the bright side, the bigot-y stuff is almost nonexistent save the description of the ill-fated cook, Hax ("quarter yellow"). Whether this was a bi-product of the revisions, I do not know (or recall), but it was a nice respite.

Scary? (0-nope to 10-you will die): 1. While there are intense scenes of violence, even the scariest stuff (slow mutants) isn't terribly scary.

Warnings: Heavy-handed tinkering, irrational editing, forced revisionist tomfoolery, author-induced spoiler alerts, cockadoodie rewrites. On the bright side, the bigot-y stuff is almost nonexistent save the description of the ill-fated cook, Hax ("quarter yellow"). Whether this was a bi-product of the revisions, I do not know (or recall), but it was a nice respite.

Artifact: The Internet Archive wins the day (and every day, knock on wood)! This time I read the scanned in Plume paperback. It was in good condition (no stains) and evenly scanned (no cut pages). I continue to be incredibly grateful to have a resource like the Internet Archive still available to me (and those like me). According to the CDC website, as of today 8/8, there have been 4.8 million cases and almost 159,000 deaths in the US from Covid 19. Members of my household have been hospitalized for respiratory illnesses in the past and none of us can take any chances contracting this disease. As a former smoker who suffered from chronic shortness of breath, I cannot fathom a more horrible way to die than drowning in your own lungs. The fact that there is no strong, centralized governing body that could have controlled the messaging, the lockdowns, and the subsequent flattening of the curve country wide is heartbreaking and infuriating. While witnessing others go about their lives as if nothing has changed while I scuttle to pick up groceries & prescriptions masked up and sanitizer at the ready, my fury only intensifies. The only comfort has been the voices of others like us piping up on social media to ask, "Am I the only one still sequestering?" only to be met by an avalanche of replies yelling, "Me, too! Me, too!" It is shocking how many people simply do not care about the welfare of others.

So even though the libraries are open (though not entirely), I cannot bear the idea of going and picking up books to take home and read. I don't know what they are doing to disinfect the books, if anything, but it isn't enough. They're made of paper, so really what could they do? One of the things I was working on pre-Covid was my germaphobia, something I was directly confronting by checking out books from the library. Here is the thing, though: It's not like I just lolled in bed and fell asleep reading them or anything so . . . normal. Nope! Hell to the nope. I would get out my lap desk and sit rigidly upright on my bed, touching nothing but the book. If I needed a break for anything, I would wash my hands first. When I was done, I'd tuck it away and wash my hands again. Once the book was finished and safely returned to the library, I would disinfect the lap desk. Being able to do any of this at all was an immense improvement from the days when I could not even enter a library, let alone touch the books or check anything out.

As glum as it makes me to even consider it, this is the first true reason I've found to finally buy an e-reader. As long as the Internet Archive continues to deliver, I can push those ugly thoughts aside, but for the first time ever, I see the appeal.